Amtrak

Union Station, the headquarters of Amtrak in Washington, D.C.

An electric Amtrak train with two AEM-7 locomotives running through New Jersey on the Northeast Corridor.

The Coast Starlight at San Luis Obispo, CA.

The Carolinian stopping in Raleigh, North Carolina in "Phase V" livery.

Amtrak station in Greensboro, NC.

Amtrak's logo from 1971 to 2000, the "inverted arrow," dubbed by critics as the "pointless arrow." On July 6, 2000 Amtrak unveiled "...a new logo whose shape and suggestion of movement convey the comfort and uniqueness of the rail experience."[1]

|

||||||||||||||||||

The National Railroad Passenger Corporation, doing business as Amtrak (reporting mark AMTK), is a government-owned corporation that was organized on May 1, 1971, to provide intercity passenger train service in the United States. "Amtrak" is a portmanteau of the words "America" and "track".[2] It is headquartered at Union Station in Washington, D.C.[3]

All of Amtrak's preferred stock is owned by the U.S. federal government. The members of its board of directors are appointed by the President of the United States and are subject to confirmation by the United States Senate. Common stock was issued in 1971 to railroads that contributed capital and equipment; these shares convey almost no benefits[4] but their current holders[5] declined a 2002 buy-out offer by Amtrak.[6]

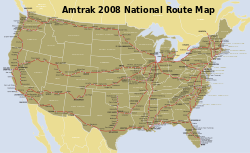

Amtrak employs nearly 19,000 people. It operates passenger service on 21,000 miles (34,000 km) of track primarily owned by freight railroads connecting 500 destinations in 46 states[7] and three Canadian provinces. In fiscal year 2008, Amtrak served 28.7 million passengers, representing six straight years of record ridership.[7][8] Despite this recent growth, the United States still has one of the lowest inter-city rail usages in the developed world.

Contents

|

History

Amtrak's origins are traceable to the sustained decline of private passenger rail services in the United States from about 1920 to 1970. In 1971, in response to the decline, Congress and President Nixon created Amtrak. The Nixon administration secretly agreed with some railroads that Amtrak would be shut down after two years. After Fortune magazine exposed the manufactured mismanagement in 1974, Louis W. Menk, chairman of the Burlington Northern Railroad remarked that the story was undermining the scheme to dismantle Amtrak.[9] Though for its entire existence the company has been subjected to political cross-winds and insufficient capital resources, including owned railway, Amtrak's ridership has maintained consistent growth.

Passenger rail service before Amtrak

From the middle 1800s until approximately 1920, nearly all intercity travelers in the United States moved by rail. By 1910, close to all of intercity passenger trips were by railroad.[10] The rails and the trains were owned and operated by private, for-profit organizations. Approximately 65,000 railroad passenger cars operated in 1929.[11]

For a long time after 1920, passenger rail's popularity diminished and there were a series of pullbacks and tentative recoveries. Rail passenger revenues declined dramatically between 1920 and 1934 because of the rise of the automobile,[10] but in the mid-1930s, railroads reignited popular imagination with service improvements and new, diesel-powered streamliners, such as the gleaming silver Pioneer Zephyr and Flying Yankee.[10] Even with the improvements, on a relative basis, traffic continued to decline, and by 1940 railroads held 67% of passenger-miles in the United States.[10] World War II broke the malaise. During the war, troop movements and restrictions on automobile fuel generated a sixfold increase in passenger traffic from the low point of the Depression.[10] After the war, railroads rejuvenated overworked and neglected fleets with fast and often luxurious streamliners — epitomized by the Super Chief and California Zephyr — which inspired the last major resurgence in passenger rail travel.

The postwar resurgence was short-lived. In 1946, there remained 45% fewer passenger trains than in 1929,[10] and the decline quickened despite railroad optimism. Passengers disappeared and so did trains. Few trains generated profits; most produced losses. Broad-based passenger rail deficits appeared as early as 1948[10] and by the mid-1950s railroads claimed aggregate annual losses on passenger services of more than $700 million (almost $5 billion in 2005 dollars using CPI).[11][12][13] By 1965, only 10,000 rail passenger cars were in operation, 85% fewer than in 1929.[11] Passenger service was provided on only 75,000 miles (120,000 km) of track, a stark decline.[11] Passenger rail service in the United States showed the signs of underinvestment. Rail facilities suffered from decrepit equipment, cavernous and nearly empty stations in declining urban centers, and management that seemed intent on driving away the few remaining customers. The 1960s also saw the end of railway post office revenues, which had helped some of the remaining trains break even.[14]

Causes of decline of passenger rail

The causes of the decline of passenger rail in the United States were complex. Until 1920, rail was the only practical form of intercity transport, but the industry was subject to government regulation and labor inflexibility.[15][16] By 1930, the railroad companies had constructed, with private funding, a vast and relatively efficient transportation network, but when the federal government began to construct the National Highway System, the railroads found themselves faced with unprecedented competition for passengers and freight with automobiles, buses, trucks, and aircraft, all of which were heavily subsidized by the government road and airport building programs. At the same time the railroads were subject to property and other taxes. Every foot of rail was taxed, and some localities treated them like cash cows. In 1916, the amount of track in the United States peaked at 254,251 miles (409,177 km), compared to 140,695 miles (226,427 km) in 2007 (although it remained the largest rail network of any country in the world).[17][18] Some routes had been built primarily to facilitate the sale of stock in the railroad companies; they were redundant from the beginning. These were the first to be abandoned as the railroads' financial positions deteriorated, and the rails were routinely removed to save money on taxes. Many rights of way were destroyed by being broken up and built over, but others remained the property of the railroad or were taken over by local or state authorities and turned into rail trails, which could be returned to rail service if necessary. To date, no rail trail in the U.S. has reverted to an active railroad.

Government regulation and labor issues

The first interruption in passenger rail's vibrancy coincided with government intervention. From approximately 1910 to 1921, the federal government introduced a populist rate-setting scheme, followed by nationalization of the rail industry for World War I. Ample railroad profits were erased, growth of the rail system was reversed, and railroads massively underinvested in passenger rail facilities during this time.[16] Meanwhile, labor costs advanced, and with them passenger fares, which discouraged passenger traffic just as automobiles gained a foothold.[16]

The primary regulatory authority affecting rail interest from early twentieth century was the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). The ICC played a leading role in rate-setting and intervened in other ways detrimental to passenger rail. Increases in train speeds which had been occurring since the 1930s were hampered after the Naperville train disaster of 1946 and other crashes in New York in 1950. The commission began limiting speeds in 1947[19][20] and in 1951 enacted a rule requiring expensive enhanced signaling for all trains traveling above a 79 mph (127 km/h) speed limit, technology that was not widely implemented outside the Northeast.[21] In 1958, the ICC was granted authority to allow or reject modifications and eliminations of passenger routes (train-offs).[22] Many routes required beneficial pruning, but the ICC delayed action by an average of eight months and when it did authorize modifications, the ICC insisted that unsuccessful routes be merged with profitable ones. Thus, fast, popular rail service was transformed into slow, unpopular service.[15] The ICC was even more critical of corporate mergers. Many combinations, which railroads sought to complete, were delayed for years and even decades, such as the merger of the New York Central Railroad and Pennsylvania Railroad, into what eventually became Penn Central, and the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad and Erie Railroad into the Erie Lackawanna Railway. By the time the ICC approved the mergers in the 1960s, disinvestments by the federal government, years of deteriorating equipment and station facilities and the flight of passengers to the air and car had taken their toll and the mergers were unsuccessful.

Taxation

At the same time, railroads carried a substantial tax burden. A World War II–era excise tax of 15% on passenger rail travel survived until 1962.[23] Local governments, far from providing needed support to passenger rail, viewed rail infrastructure as a ready source for property tax revenues. In one extreme example, in 1959 the Great Northern Railway, which owned about a third of one percent (0.34%) of the land in Lincoln County, Montana, was assessed more than 91% of all school taxes in the county.[15] To this day, railroads are generally taxed at a higher rate than other industries, and the rates vary greatly from state to state.[24]

Railroads also were saddled with antiquated work rules and an inflexible relationship with trade unions. Work policies did not adapt to technological change.[15] Average train speeds doubled from 1919 to 1959, but unions resisted efforts to modify their existing 100 to 150 mile work days. As a result, railroaders' work days were roughly cut in half, from 5–7½ hours in 1919 down to 2½-3¾ hours in 1959. Labor rules also perpetuated positions that had been obviated by technology. Between 1947 and 1957, passenger railroad financial efficiency dropped by 42% per mile.

Today, the burden of nascent railroad worker pensions, including those of freight railroad workers, are financed by Amtrak, regardless of whether such workers were ever employed by Amtrak or worked in passenger railroad service. In effect, Amtrak subsidizes the pensions of thousands of railroad workers who would otherwise not receive any pension.[25]

Subsidized competition

While passenger rail faced internal and governmental pressures, new challenges appeared that undermined the dominance of passenger rail: highways and commercial aviation. The passenger rail industry wilted as government backed these potent upstarts with billions of dollars in construction of highways and government-owned airports and the air traffic control system.

As cars became more attainable to most Americans, this newfound freedom and individualization of transit became the norm for most Americans because of the increased convenience. Government actively began to respond with funds from its treasury and later with fuel tax funds to build a non-profit network of roads not subject to property taxation[26] that rivaled and then surpassed the for-profit network that the railroads had built in previous generations with corporate capital and government land grants. All told between 1921 and 1955 governmental entities, using taxpayer money and in response to taxpayer demand, financed more than $93 billion worth of pavement, construction, and maintenance.[15]

In the 1950s, a second and more formidable threat appeared: affordable commercial aviation. Government at many levels supported aviation. Governmental entities built sprawling urban and suburban airports, funded construction of highways to provide access to the airports, and provided air traffic control services.

Loss of U.S. Mail Contracts

Until 1966, most U.S. Postal Service mail was transported on passenger trains. By the 1960s, it was not uncommon for passenger trains to feature a dozen mail cars with only a few passenger cars. The mail contracts kept most passenger trains economically viable. In 1966, the U.S. Postal Service switched to trucks and airplanes, depriving many passenger trains of a major source of revenue.

Rail Passenger Service Act

In the late 1960s, the end of passenger rail in the United States seemed near. First had come the requests for termination of services; now came the bankruptcy filings. The legendary Pullman Company became insolvent in 1969, followed by the dominant railroad in the Northeastern United States, the Penn Central, in 1970. It now seemed that passenger rail's financial problems might bring down the railroad industry as a whole. Few in government wanted to be held responsible for the extinction of the passenger train, but another solution was necessary.

In 1970, Congress passed and President Richard Nixon signed into law, the Rail Passenger Service Act. Proponents of the bill, led by the National Association of Railroad Passengers (NARP), sought government funding to assure the continuation of passenger trains. They conceived the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (NRPC), a hybrid public-private entity that would receive taxpayer funding and assume operation of intercity passenger trains. The original working brand name for NRPC was Railpax, but shortly before the company started operating it was changed to Amtrak. There were several key provisions:

- Any railroad operating intercity passenger service could contract with the NRPC, thereby joining the national system.

- Participating railroads bought into the NRPC using a formula based on their recent intercity passenger losses. The purchase price could be satisfied either by cash or rolling stock; in exchange, the railroads received NRPC common stock.

- Any participating railroad was freed of the obligation to operate intercity passenger service after May 1, 1971, except for those services chosen by the Department of Transportation as part of a "basic system" of service and paid for by NRPC using its federal funds.

- Railroads that chose not to join the NRPC system were required to continue operating their existing passenger service until 1975 and thenceforth had to pursue the customary Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) approval process for any discontinuance or alteration to the service.

Nearly everyone involved expected the experiment to be short-lived. The Nixon administration and many Washington insiders viewed the NRPC as a politically expedient way for the President and Congress to give passenger trains the one "last hurrah" demanded by the public. They expected Amtrak to quietly disappear as public interest waned.[27] Proponents also hoped that government intervention would be brief, but their view was that Amtrak would soon support itself. Neither view has proved correct. Popular support has allowed Amtrak to continue in operation longer than critics imagined, while financial results have made a return to private operation unfeasible.

Non-participating railroads

Only six railroads that were still offering long-distance passenger service declined to join Amtrak in 1971.[28]

- Chicago South Shore and South Bend Railroad trains were taken over by the Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District.

- Georgia Railroad – Required by its state charter to maintain a minimal passenger service, which it did on its mixed freight/passenger trains until the company was sold to the Seaboard System in 1983.

- Reading's service from Philadelphia to Newark Penn Station, Bethlehem, PA, and Pottsville, PA, continued into Conrail. Service to Bethlehem and Pottsville was discontinued in 1981, as well as through service to Newark beyond West Trenton.

- Rio Grande – Continued operating its Rio Grande Zephyr, a truncated version of the famous California Zephyr, until 1983. At that time Amtrak rerouted its California Zephyr to follow the DRG's more scenic route between Denver and Salt Lake City.

- Rock Island – The fee to join Amtrak was determined to be more than the out-of-pocket cost of continuing to operate its remaining intercity passenger trains for the statutory five years, so the Rock Island continued operating two truncated passenger trains (the Peoria Rocket and the Quad Cities Rocket) on short routes out of Chicago until 1978.

- Southern – Operated the Southern Crescent and three other trains over its own rails until relinquishing operation of the train to Amtrak in 1979. Southern's subsidiary, the Central of Georgia, did join and its trains were discontinued.

Early days

Amtrak began operations May 1, 1971. Amtrak's first passenger train, Train 173 (Clocker), departed New York Penn Station at 12:05 a.m. on May 1 en route to Philadelphia 30th Street Station with a GG1 inherited from Penn Central. The corporation was molded from the passenger rail operations of 20 out of 26 major railroads in operation at the time. The railroads contributed rolling stock, equipment, and capital. In return, they received approval to discontinue their passenger services, and at least some acquired common stock in Amtrak. Amtrak received no rail tracks or right-of-way at its inception. Railroads that shed passenger operations were expected to host Amtrak trains on their tracks, for a fee.

There was a period of adjustment. However, Amtrak was making numerous renovations and improvements. All Amtrak's routes were continuations of prior service, although Amtrak pruned about half the passenger rail network. Of the 364 trains operated previously, Amtrak only continued 182. On trains that continued, to the extent possible, schedules were retained with only minor changes from the Official Guide of the Railways. Former names largely were continued.

Several major corridors became freight-only, including New York Central Railroad's Water Level Route across New York and Ohio and Grand Trunk Western Railroad's Chicago to Detroit service, although service soon returned to the Water Level Route with introduction of the Lake Shore Limited. Reduced passenger train schedules created headaches. A 19-hour layover became necessary for eastbound travel on the James Whitcomb Riley between Chicago and Newport News.

Amtrak inherited problems with train stations, most notably deferred maintenance, and redundant facilities resulting from competing companies that served the same areas. On the day it started, Amtrak was given the responsibility of rerouting passenger trains from the seven train terminals in Chicago (LaSalle, Dearborn, Grand Central, Randolph, Chicago Northwestern Terminal, Central, and Union) into just one, Union Station. In New York City, Amtrak had to pay to maintain Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal because of the lack of track connections to bring trains from upstate New York into Penn Station, a problem not rectified until the building of the Empire Connection in 1991. In many cases Amtrak had to abandon service into the huge old Union Stations such as Cincinnati, Saint Paul, Buffalo, Kansas City, Houston, and Saint Louis, and route trains into smaller Amtrak-built facilities down the line, jokingly referred to over the years as "Amshacks" due to their basic design. Amtrak has pushed to start reusing some of the old stations, most recently Cincinnati Union Terminal, and Kansas City Union Station.

On the other hand, merged operations presented efficiencies such as the combination of three West Coast trains into the Coast Starlight, running from Los Angeles to Seattle. The Northeast Corridor received an Inland Route via Springfield, Massachusetts, thanks to support from New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts. The North Coast Hiawatha was implemented as a second Pacific Northwest route. The Milwaukee to St. Louis Abraham Lincoln and Prairie State routes also commenced. The first all-new Amtrak route, not counting the Coast Starlight, was the Montrealer/Washingtonian. That route was inaugurated September 29, 1972, along Boston and Maine Railroad and Canadian National Railway track that had last seen passenger service in 1966. Amtrak was also instrumental in restoring service in the Empire Corridor of upstate New York, between Albany and Niagara Falls, with its Empire Service, a service that was discontinued in the sixties by the New York Central and Penn Central.

Amtrak soon had the opportunity to acquire railway. Following the bankruptcy of several northeastern railroads in the early 1970s, including Penn Central which owned and operated the Northeast Corridor, Congress passed the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976. A large part was directed to the creation of a Conrail, but in addition the law enabled transfer to Amtrak of the Northeast Corridor railway from Boston, Massachusetts to Washington, D.C. That track became Amtrak's jewel and helped Amtrak generate significant revenues. While the Northeast Corridor ridership and revenues were higher than any other segment of the system, the cost of operating and maintaining the corridor proved to be overwhelming. As a result, Amtrak's federal subsidy increased dramatically. In subsequent years, short route segments not needed for freight operations were transferred to Amtrak. Nevertheless, in general, Amtrak remained dependent on freight railroads for access to most of its routes outside of the northeast.

Amtrak's early years are often called the "Rainbow Era," which refers to the ad hoc arrangement of the rolling stock and locomotives from the various eligible donor railroads. This rolling stock, which for the most part still bore the pre-Amtrak colors and logos, formed the multi-colored consists of early Amtrak trains. By mid-1971, Amtrak began purchasing some of the equipment it had leased, including 286 second-hand E and F units, 30 GG1 electric locomotives, and 1290 passenger cars, and continued leasing even more motive power. By 1975 the official Amtrak color scheme was painted on most Amtrak equipment. Newly purchased locomotives and rolling stock began appearing by 1975 as well.[29]

Amtrak fell far short of financial independence in its first decade, but it did find modest success rebuilding trade. Outside factors discouraged competing transport, such as fuel shortages which increased costs of automobile and airline travel, and strikes which disrupted airline operations. Investments in Amtrak's track, equipment and information also made Amtrak more relevant to America's transportation needs.[30][31] Amtrak's ridership increased from 16.6 million in 1972 to 21 million in 1981.[32]

Leaders and political influences

Unlike many large businesses, subsequent to its formation Amtrak has had only one active investor: the U.S. government. Like most investors, the federal government has demanded a degree of accountability. Determination of congressional funding and selection of Amtrak's leadership have been infused with political considerations. As discussed below, funding levels and capital support have varied over time.

Like many railroads, some members of Amtrak's board have had little or no experience with railroads. Conversely, Amtrak also has benefited from the interest of highly motivated and politically oriented public servants. For example, in 1982, former Secretary of the Navy and retired Southern Railway head W. Graham Claytor, Jr. brought his military and railroad experience to the job. Graham Claytor earned distinction as a lawyer (he was president of the Harvard Law Review and law clerk to U.S. Judge Billings Learned Hand and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis); as a transportation executive (he joined the Southern as vice president-law in 1963, became president in 1967, and retired in 1977, five years before he took over the command at Amtrak); and as a public servant (he was President Carter's Secretary of the Navy, Deputy Secretary of Defense, and, briefly, Acting Secretary of Transportation, all between his two railroad careers). Claytor came out of retirement to lead Amtrak after the disastrous financial results during the Carter administration (1977–1981).[33] He was recruited by then Secretary of Transportation, Drew Lewis, and Federal Railroad Administrator Robert Blanchette, both Reagan appointees. Despite the fact that Claytor frequently opposed the Reagan Administration over Amtrak funding issues, he was strongly supported by John H. Riley, an attorney who was the highly skilled head of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) under the Reagan Administration from 1983–1989. Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole also tacitly supported Amtrak. Claytor, the longest serving Amtrak CEO at 12 years, clearly enjoyed a good relationship with the Congress and was perceived by many in the rail industry and government to have done an outstanding job of running Amtrak. Due to limited federal funding, Claytor was forced to use short-term debt to keep most of its operations running.[34] 1988 Democratic Presidential nominee Michael Dukakis served as Amtrak's vice chairman of the board and was nominated as a director by President Clinton in 1998.

In the 1990s, Claytor was succeeded at Amtrak's helm by a succession of career public servants. First, Thomas Downs, who had overseen the Union Station project in Washington, D.C., which experienced substantial delays and cost overruns, assumed the leadership. Amtrak faced a serious cash crisis during 1997. However, Tim Gillespie, Amtrak's highly regarded vice president for government affairs for almost two decades, persuaded Congress to include a provision in the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 that resulted in Amtrak receiving a $2.3 billion tax refund that resolved their cash crisis.[35] In January, 1998, after Amtrak weathered this serious cash shortfall, George Warrington succeeded Downs. Warrington previously led Amtrak's Northeast Corridor Business Unit. Warrington ran into trouble with Congress and the Administration through lavish spending and extensive borrowing. When he attempted to mortgage Penn Station in New York City he ran into a fire storm of opposition in Congress. Warrington stepped down shortly thereafter.

In April 2002, David L. Gunn was selected as president. Gunn had a strong reputation as a straightforward and experienced manager. Years earlier (between 1991 and 1994), Gunn's refusal to "do politics" put him at odds with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority board of directors, which included representatives from the District of Columbia and suburban jurisdictions in Maryland and Virginia. Gunn was an accomplished public servant and railroad person and his successes before Amtrak earned him a great deal of credibility, despite a sometimes-rough relationship with politicians and labor unions.

Gunn was polite but direct in response to congressional criticism of Amtrak, and his tenure was punctuated by successes in reducing layers of management overhead in Amtrak and streamlining operations. Amtrak's Board of Directors removed Gunn on November 9, 2005. The board then appointed David Hughes, Amtrak's Chief Engineer, as interim CEO.[36] Given Gunn's solid performance, many Amtrak supporters feared that Gunn's departure was Amtrak's death knell, although those fears have not been realized. On August 29, 2006 Alexander Kummant was named as Gunn's permanent replacement effective September 12, 2006.[37] Kummant resigned on November 14, 2008. The board appointed Amtrak COO William Crosbie as interim CEO.[38] On November 26, 2008, the board appointed Federal Railroad Administration chairman Joseph H. Boardman as interim Amtrak President and CEO for one year.[39] In January 2010, Amtrak announced that they had extended Boardman's appointment indefinitely.[40]

The list of Presidents of Amtrak includes:

- Roger Lewis (1971–1974)[41]

- Paul Reistrup (1974–1978)[42]

- Alan Stephenson Boyd (1978–1982)[43][44]

- W. Graham Claytor, Jr. (1982–1993)[45]

- Thomas Downs (1993–1998)[46]

- George Warrington (1998–2002)[47]

- David L. Gunn (2002–2005)[36][48]

- David Hughes (interim) (2005–2006)[36]

- Alexander Kummant (2006–2008)[37][49]

- William Crosbie (interim) (2008)

- Joseph H. Boardman (2008–present)[39][50]

Amtrak's Board of Directors consists of the following people (updated July 2010):[51]

- Chairman Thomas Carper

- Vice-Chairman Donna McLean

- Joseph Boardman

- Anthony Coscia

- Albert DiClemente

- Ray LaHood

- Jeffrey Morland

- Nancy Naples

- One seat is vacant.

Modern history (1980s to present)

Ridership stagnated at roughly 20 million passengers per year amid uncertain government aid from 1981 to about 2000.[32][52] Ridership increased in the 2000s after implementation of capital improvements in the Northeast Corridor and rises in automobile fuel costs. Amtrak set its sixth straight year of record ridership, with 28.7 million passengers for the 12 months ended September 30, 2008.[53] According to Amtrak, an average of more than 70,000 passengers ride on up to 300 Amtrak trains per day.[2]

In the 1990s, Amtrak's stated goal remained operational self-sufficiency. By this time, however, Amtrak had a large overhang of debt from years of underfunding, and in the mid-1990s, Amtrak suffered through a serious cash crunch. To resolve the crisis, Congress issued funding but instituted a glide-path to financial self-sufficiency, excluding railroad retirement tax act payments.[54] Passengers became "guests" and there were expansions into express freight work, but the financial plans failed. Amtrak's inroads in express freight delivery created additional friction with competing freight operators, including the trucking industry. Delivery was delayed of much anticipated high-speed trainsets for the improved Acela Express service, which promised to be a strong source of income and favorable publicity along the Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington, D.C. Through the late 1990s and early 2000s, Amtrak could not add sufficient express freight revenue or cut sufficient other services to break even. By 2002, it was clear that Amtrak could not achieve self-sufficiency, but Congress continued to authorize funding and released Amtrak from the requirement.[55]

Amtrak's leader at the time, David L. Gunn, was polite but direct in response to congressional criticism. In a departure from his predecessors' promises to make Amtrak self-sufficient in the short term, Gunn argued that no form of passenger transportation in the United States is self-sufficient as the economy is currently structured.[56] Highways, airports, and air traffic control all require large government expenditures to build and operate, coming from the Highway Trust Fund and Aviation Trust Fund paid for by user fees, highway fuel and road taxes, and, in the case of the General Fund, by people who own cars and do not.[57]

Before a congressional hearing, Gunn answered a demand by leading Amtrak critic Arizona Senator John McCain to eliminate all operating subsidies by asking the Senator if he would also demand the same of the commuter airlines, upon which the citizens of Arizona are dependent. McCain, usually not at a loss for words when debating Amtrak funding, did not reply.[58]

Under Gunn, almost all the controversial express freight business was eliminated. The practice of tolerating deferred maintenance was reversed to eliminate a safety issue.[59]

Amtrak's previous chief, Alexander Kummant, was committed to operating a national rail network, and he did not envision separating the Northeast Corridor (the rail line from Washington, DC, to Boston that is primarily, though not completely, owned by Amtrak) under separate ownership. He said that shedding the system's long distance routes would amount to selling national assets that are on par with national parks, and that Amtrak's abandonment of these routes would be irreversible. Amtrak is seeking annual congressional funding of $1 billion for ten years. Kummant has stated that the investment is moderate in light of federal investment in other modes of transportation.[60]

Public funding

Amtrak commenced operations in 1971 with $40 million in direct federal aid, $100 million in federally insured loans, and a somewhat larger private contribution.[61] Officials expected that Amtrak would break even by 1974, but those expectations proved unrealistic and annual direct Federal aid reached a 17-year high in 1981 of $1.25 billion.[62] During the Reagan administration, appropriations were halved. By 1986, federal support fell to a decade low of $601 million, almost none of which were capital appropriations.[63] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Congress continued the reductionist trend even while Amtrak expenses held steady or rose. Amtrak was forced to borrow to meet short-term operating needs, and by 1995 Amtrak was on the brink of a cash crisis and was unable to continue to service its debts.[64] In response, in 1997 Congress authorized $5.2 billion for Amtrak over the next five years—largely to complete the Acela capital project—on the condition that Amtrak submit to the ultimatum of self-sufficiency by 2003 or liquidation.[65] Amtrak made financial improvements during the period, but ultimately did not achieve self-sufficiency.

In 2004, a stalemate in federal support of Amtrak forced cutbacks in services and routes as well as resumption of deferred maintenance. In fiscal 2004 and 2005, Congress appropriated about $1.2 billion for Amtrak, $300 million more than President George W. Bush had requested. However, the company's board requested $1.8 billion through fiscal 2006, the majority of which (about $1.3 billion) would be used to bring infrastructure, rolling stock, and motive power back to a state of good repair. In Congressional testimony, the Department of Transportation's inspector-general confirmed that Amtrak would need at least $1.4 billion to $1.5 billion in fiscal 2006 and $2 billion in fiscal 2007 just to maintain the status quo. In 2006, Amtrak received just under $1.4 billion, with the condition that Amtrak would reduce (but not eliminate) food and sleeper service losses. Thus, dining service were simplified and now require two fewer on-board service workers. Only Auto Train and Empire Builder services continue regular made on-board meal service. In 2010 the Senate approved a bill to provide $1.96 billion to Amtrak, but cut the approval for high speed rail to a $1 billion appropriation.[66]

State governments have partially filled the breach left by reductions in federal aid. Several states have entered into operating partnerships with Amtrak, notably California, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Michigan, Oregon, Missouri, Washington, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Vermont, Maine, and New York, as well as the Canadian province of British Columbia, which provides some of the resources for the operation of the Cascades route.

With the dramatic rise in gasoline prices during 2007–2008, Amtrak has seen record ridership.[67] Capping a steady five-year increase in ridership overall, regional lines saw 12% year-over-year growth in May 2008.[68] In October 2007, the Senate passed S-294, "Passenger Rail Improvement and Investment Act of 2007" (70–22) sponsored by Senators Frank Lautenberg and Trent Lott. Despite a veto threat by President Bush, a similar bill passed the House on June 11, 2008 with a veto-proof margin (311–104).[69] The final bill, spurred on by the September 12 Metrolink collision in California and retitled "Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008", was signed into law by President Bush on October 16, 2008. The bill appropriates $2.6 billion a year in Amtrak funding through 2013.[70]

Controversy

Government aid to Amtrak was controversial from the beginning. The formation of Amtrak in 1971 was criticized as a bailout serving corporate rail interests and union railroaders, not the traveling public. Critics assert that Amtrak has proven incapable of operating as a business and that it does not provide valuable transportation services meriting public support,[71] a "mobile money-burning machine."[72] They argue that subsidies should be ended, national rail service terminated, and the Northeast Corridor turned over to private interests. "To fund a Nostalgia Limited is not in the public interest."[73] Critics also question Amtrak's energy efficiency, though[74] the U.S. Department of Energy considers Amtrak among the most energy-efficient forms of transportation.[75]

Proponents point out that the government heavily subsidizes the Interstate Highway System, the Federal Aviation Administration, many airports, among many aspects of passenger aviation. Massive government aid to those forms of travel was a primary factor in the decline of passenger service on privately owned railroads in the 1950s and 1960s. In addition, Amtrak pays property taxes (through fees to host railroads) that highway users do not pay. Advocates therefore assert that Amtrak should only be expected to be as self-sufficient as those competing modes of transit.

Along these lines, in a June 2008 interview with Reuters,[57] Amtrak President Alex Kummant made specific observations: $10 billion per year is transferred from the general fund to the Highway Trust Fund; $2.7 billion is granted to the FAA; $8 billion goes to "security and life safety for cruise ships." Overall, Kummant claims that Amtrak receives $40 in federal funds per passenger, while highways are subsidized at a rate of $500–$700 per automobile. Moreover, Amtrak provides all of its own security, while airport security is a separate federal subsidy. Kummant added: "Let's not even get into airport construction which is a miasma of state, federal and local tax breaks and tax refinancing and God knows what."

According to the United States Department of Transportation's Bureau of Transportation Statistics, rail and mass transit are considerably more subsidized on a per passenger-mile basis by the federal government than other forms of transportation; the subsidy varies year to year, but exceeds $100 dollars (in 2000 dollars) per thousand passenger-miles, compared to subsidies around $10 per thousand passenger-miles for aviation (with general aviation subsidized considerably more per passenger-mile than commercial aviation), subsidies around $4 per thousand passenger-miles for intercity buses, and automobiles being a small net contributor through the gas tax and other user fees rather than being subsidized.[76] On a total subsidy basis, aviation, with many more passenger-miles per year, is subsidized at a similar level to Amtrak. The analysis does not consider social costs and benefits, or difficult to quantify effects of some regulation, such as safety regulation.

Critics, such as the Cato Institute's Randal O'Toole,[77] argue that gasoline taxes amount to user fees because people are taxed to the extent they use the roads. However, there is still a significant amount of road spending that is not covered by the gas tax. It covers little of the costs for local highways and in many states little of the cost for state highways.[78][79] Taking these facts into account, though, O'Toole claims on page 2 of his report that "in 2006, Americans paid $93.6 billion in tolls, gas taxes, and other highway user fees. Of this amount, $19.3 billion was diverted to mass transit and other non-highway activities. At the same time, various governments—mainly local—spent $44.5 billion in property, sales, or other taxes on highways, roads, and streets. The net subsidy to highways was $25.1 billion, or about half a penny per passenger mile." O'Toole's road budget and passenger-mile numbers are disputed. In the same year, Amtrak receives direct subsidies of just over $1 billion, or 22 cents per passenger mile.

Labor issues

Many trade union jobs were saved by the bailout, and Amtrak itself finances the pensions of most railroad employees, even if they had never worked for Amtrak directly or never worked in passenger railroad service.

In recent times, efforts at reforming passenger rail have addressed labor issues. In 1997 Congress released Amtrak from a prohibition on contracting for labor outside of the corporation (and outside its unions), opening the door to privatization.[80] Since that time, many of Amtrak's employees have been working without a contract. The most recent contract, signed in 1999, was mainly retroactive.

Still, though, the influence of unions is a strong force against change. Amtrak has 14 separate unions to negotiate with, because of the fragmentation of railroad unions by job. Plus, it has 24 separate contracts with those unions.[81] This makes it difficult to make substantial changes, in contrast to a situation where one union negotiates with one employer. Former Amtrak president Kummant seems poised to follow a cooperative posture with Amtrak's trade unions. He has ruled out plans to privatize large parts of Amtrak's unionized workforce.[82]

In late 2007 and early 2008, however, major labor issues came up, a result of a dispute between Amtrak and 16 unions over healthcare, specifically which employees healthcare should be available to. The dispute was not resolved quickly, and the situation escalated, to the point of President Bush declaring a Presidential Emergency Board to resolve the issues. It was not immediately successful, and a strike was threatened, to begin on January 30, 2008. In the middle of that month, however, it was announced that Amtrak and the unions had come to terms and January 30 passed without a strike. In late February it was announced that three more unions had worked out their differences, and as of that time it seems unlikely that any more issues will arise in the near future.

Amtrak operations and services

Amtrak is no longer required by law, but is encouraged, to operate a national route system.[83] Amtrak has some presence in all of the 48 contiguous states except Wyoming and South Dakota.[84] Service on the Northeast Corridor, between Boston, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C., as well as between Philadelphia and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is powered by overhead wires; for the rest of the system, diesel locomotives are used. Routes vary widely in frequency of service, from three trips weekly on the Sunset Limited (Los Angeles, California, to New Orleans, Louisiana), to weekday service several times per hour on the Northeast Corridor, (New York City to Washington, D.C.)[85] Amtrak also operates a captive bus service, Thruway Motorcoach, which provides connections to train routes.

The most popular and heavily used services are those running on the Northeast Corridor (NEC), which include the Acela Express, and Northeast Regional. The NEC serves Boston, Massachusetts; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Baltimore, Maryland; Washington, D.C.; and many communities between. The NEC services accounted for 10.0 million of Amtrak's 25.7 million passengers in fiscal year 2007.[86] Regional services in California, subsidized by the California Department of Transportation are the most popular services outside of the NEC and the only other services boasting over one million passengers per annum. The Pacific Surfliner, Capitol Corridor and San Joaquin services accounted for a combined 5.0 million passengers in fiscal year 2007.[86]

Four of the six stations busiest by boardings are on Amtrak's NEC: New York (Penn Station) (first), Washington (Union Station) (second), Philadelphia (30th Street Station) (third), and Boston (South Station) (sixth). The other two of the top six are Chicago (Union Station) (fourth) and Los Angeles (Union Station) (fifth).[87]

Amtrak trains have both names and numbers. Train routes are named to reflect the rich and complex history of the routes and the areas traversed by them. Each scheduled run of the route is assigned a number. Generally, even-numbered routes run northward and eastward, while odd-numbered routes run southward and westward. Some routes, such as the Pacific Surfliners, use the opposite numbering system, inherited from the previous operators of similar routes, such as the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.

These are the 15 busiest routes in the Amtrak system, ordered by region followed by ridership:

|

West Coast

|

Northeast

|

Rail passenger efficiency versus other modes

Per passenger mile, Amtrak is 30–40 percent more energy-efficient than commercial airlines and automobiles overall,[88] though the exact figures for particular routes depend on load factor along with other variables. The electrified trains in the Northeast Corridor are considerably more efficient than Amtrak's diesels and can feed energy captured from regenerative braking back to the electrical grid. Passenger rail is also competitive with other modes in terms of safety per mile.

| Mode | Revenue per passenger mile[89] | Energy consumption per passenger mile[88] | Deaths per 100 million passenger miles[90] | Reliability[91] |

| Domestic airlines | 13.0¢ | 3,210 BTUs | 0.02 deaths | 76% |

| Intercity buses | 12.9¢[92] | <1,000 BTUs | 0.05 deaths | N/A |

| Amtrak | 30.7¢ | 1,482 BTUs[92] | 0.03 deaths | 80% |

| Autos | N/A | 3,525 BTUs | 0.8 deaths | N/A |

It should be noted that on-time performance is calculated differently for airlines than for Amtrak. A plane is considered on-time if it arrives within 15 minutes of the schedule. Amtrak uses a sliding scale, with trips under 250 miles (400 km) considered late if they're more than 10 minutes behind schedule, up to 30 minutes for trips over 551 miles (887 km) in length.[91]

Intermodal connections

Intermodal connections between Amtrak trains and other transportation are available at many stations. Most Amtrak rail stations in downtown areas have connections to local public transport. Amtrak also code shares with Continental Airlines, providing service between Newark Liberty International Airport (via its Amtrak station and AirTrain Newark) and Philadelphia 30th St, Wilmington, Stamford, and New Haven. Amtrak also serves airport stations at Milwaukee, Oakland, Burbank, and Baltimore.

Amtrak coordinates Thruway Motorcoach service to extend many of its routes, especially in California.

Gaps in service

Outside the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak is a niche player in passenger transportation. In 2003, Amtrak accounted for just 0.1% of U.S. intercity passenger miles (5,680,000,000 out of 5,280,860,000,000 total, of which private-automobile travel makes up the vast majority).[93] In fiscal year 2004, Amtrak routes served over 25 million passengers, while, in calendar year 2004, commercial airlines served over 712 million passengers.[94]

When it started on May 1, 1971, Amtrak operated a fairly more truncated system of passenger trains than had previously existed. Out of the 364 passenger trains that operated on April 30, 1971, only 182 were continued. In its initial setup, Amtrak only served 46 out of the 50 states. Alaska and Hawaii were excluded due to their not being located within the contiguous United States. South Dakota had passenger rail train service offered by the Milwaukee Road up until the Amtrak takeover, however for budget reasons, it was left out of the Amtrak system. Maine also was left out because the last passenger trains in the state had ceased operation in 1967. Residents of northern New England began a lengthy battle to get Amtrak to restore service to Maine which it finally did with the successful Downeaster in 2000.

As of 2010 Amtrak still provides service to only 46 out of the 50 states. Although Maine gained service, Wyoming lost rail service in the 1997 cuts, and in early 2008 lost its Denver–Casper motorcoach service. However, even within the states they do operate within service is nominal at best. Many trains operate along borders and/or away from major population areas, such as in Idaho or in Kentucky. Many major cities in the Midwest, West, and South have two or fewer trains per day, such as Atlanta, Denver, Cincinnati, Houston, Indianapolis, and Minneapolis – Saint Paul.

Since its inception, Amtrak has been reliant on freight railroads and operating over their rights of way. Thus Amtrak services are affected if a freight railroad decides to abandon a right of way that its uses. This can sometimes lead to a rerouting of a train over a different route, adding to a train's travel time, or to the complete discontinuance of a train. Several trains affected by freight railroads over the years have been:

- The Silver Palm, later renamed the Palmetto, used to run a route between New York and St. Petersburg, Florida. In 1983 it was truncated to Tampa, Florida because Amtrak was unable to take on the costs of maintaining the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad drawbridge, which took the train over Tampa Bay. Likewise in 2004 service on the Palmetto was further truncated back to Savannah, Georgia, when CSX, successor to the Seaboard Coast Line, decided to abandon its mainline through Gainsville and Ocala, which was the route for Palmetto on its way to Tampa.

- The Sunset Limited was rerouted in 1997 to skip Phoenix, Arizona, after the Union Pacific Railroad decided to abandon the trackage that served Phoenix. Amtrak did not have the funds to maintain the trackage and thus the city proper is served only by Thruway Motorcoach. Amtrak rail service is available about 37 miles (60 km) to the south in the rural town of Maricopa (Phoenix passengers also travel often, by car or Greyhound bus, to Tucson to pick up the Sunset Limited or Flagstaff to pick up the Southwest Chief).

- The San Joaquin service through central California, which is the primary connection for Los Angeles with Sacramento and Oakland, California, is one of the most noticeable freight interruptions affecting Amtrak trains. Between Los Angeles's Union Station and Bakersfield's Truxtun Avenue Station passengers must take an Amtrak motorcoach bus service to connect with the train in Bakersfield. This is because the trackage between Bakersfield and Mojave on this route, owned and operated by Union Pacific, known as the Tehachapi Pass, is the busiest single freight route in the country and thus UP prohibits passenger trains from using the route. The 280 to 318-mile route thus takes roughly nine hours. The only direct connection between Los Angeles and Oakland is through the daily Seattle to Los Angeles Coast Starlight which runs along the Pacific Coast, however, on a much longer twelve-hour schedule.

Several significant Amtrak routes have been eliminated because of lack of funding since 1971, creating other gaps such as:

- The National Limited, a New York and Washington D.C. train that connected with Kansas City, Missouri, providing direct connections to cities such as Pittsburgh, Columbus, Ohio, Indianapolis, and St. Louis. After its discontinuance in 1979, Chicago was left as the only throughway for direct links between the Midwest and East.

- The North Coast Hiawatha, between Chicago and Seattle, had supplemented the Empire Builder service to the Pacific Northwest. The Hiawatha provided communities along the corridor with much needed Amtrak service and also provided an additional daily service between Chicago and Minneapolis–St. Paul. It was cut in 1979.

- The Floridian, which was the last link with the vaunted Chicago–Florida services of such trains as the City of Miami, the Dixie Flagler, and the South Wind, was discontinued in October 1979 along with the Louisville, Kentucky to Sanford, Florida Auto Train that the Floridian connected to in Louisville. This left the Midwest without any direct connections to Florida. Today passengers must travel east to Washington, D.C. to connect with the southbound Silver Star and Silver Meteor.

- In 1986 the local Minneapolis/Saint Paul to Duluth, Minnesota service the North Star was eliminated and replaced with through motorcoach service.

- In 1997, the Desert Wind and Pioneer were discontinued. These cuts were significant due to the fact that it eliminated Amtrak service from a large service area such as Las Vegas, Boise, and all of Wyoming.

- In 2003, Amtrak discontinued the Kentucky Cardinal, ending all service to Louisville.

- In 2005, Three Rivers (a reborn Broadway Limited) was canceled, removing the only direct New York–Chicago service through central Pennsylvania.

One service that had been affected by both freight interruptions and service cuts is the Sunset Limited, the thrice-weekly train between Orlando and Los Angeles. Track damage along the Gulf Coast caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 resulted in the train being temporarily truncated to New Orleans. Although the track's owner, CSX, completed repairs by early 2006, Amtrak service has not resumed over four years later, leaving the intermediate stations between Jacksonville, Florida and New Orleans without any Amtrak service. Many Gulf Coast residents and politicians believe that Amtrak, longing to discontinue the route, used the hurricane as an excuse to suspend service. Currently (as of 2010)Amtrak is under pressure from Congress to restore the route.

Additionally, cities that are sufficiently served by Amtrak don't always have direct connections with other cities nearby. Little Rock, Arkansas (Texas Eagle) and Memphis, Tennessee (City of New Orleans) both have Amtrak service, yet there is no longer a direct connection between the two cities. Passengers wanting to travel between them must venture to Chicago to the north or New Orleans to the south and change trains in order to get there.

Recent issues with freight railroads

- According to August 2010 issue of Trains Magazine, the Southwest Chief currently faces some challenges regarding some moves made by BNSF to cease all freight operations between La Junta, CO, and Lamy, NM. It has been reported that BNSF told Amtrak that as of January 1, 2010, all maintenance costs are to be covered by Amtrak if they wished to continue routing the train over the same right-of-way. Furthermore, BNSF has also declared that it will maintain the tracks between Hutchinson, KS, and La Junta, CO, at a Class 2 (30 mph passenger train maximum) speed instead of a Class 4 (79 mph passenger train maximum), again handing the bill over to Amtrak if they wanted to see service continue at a Class 4 level. These moves have led BNSF to offer to host the Southwest Chief over BNSF's currently used freight routes via Wichita, KS, Wellington, KS, Amarillo, TX, and Clovis, NM; however, Amtrak has refused and insists that they will pay the bill in order to keep the service as it currently is.[95]

- Three intermediate stops along the route of the Empire Builder in North Dakota are on the chopping block due to complications arising from Devils Lake, also according to the August 2010 issue of Trains Magazine. Because Canada will not allow the waters of the lake to drain within its borders, the lake is slowly rising and threatens to submerge the BNSF right-of-way located near it. As a result, BNSF has ended freight service between Devils Lake and Churchs Ferry, handing the cost of maintenance over to Amtrak. North Dakota's Congressional delegation have declared that there will be no reroute, as suggested by BNSF, to go directly between Fargo, ND, and Minot, ND, and possibly serve New Rockford, ND; instead, they have declared that they will "find the necessary funding needed" in order to help Amtrak cover the maintenance costs.[95]

Train speeds, frequency and usage (ridership): international comparisons

By European and Japanese standards, the speed of intercity Amtrak trains (outside of the Northeast Corridor) is regarded as extremely slow. This is in large part because most Amtrak intercity service operates on the trackage of the major freight railroads. Freight rail operators are required under federal law to give dispatching preference to Amtrak trains, but some railroads routinely violated or skirted regulations for many years, resulting in trains sitting idle on the track for as long as an hour or more while waiting for freight traffic to clear. The railroads' dispatching practices were investigated in 2008,[96] resulting in stricter laws about train priority which had a dramatic impact. Amtrak's overall on-time performance went up from 74.7% in fiscal 2008 to 84.7% in 2009, with long-distance trains and others outside the Northeast Corridor seeing the greatest benefit. The Missouri River Runner jumped from a very poor 11% to 95%, becoming one of Amtrak's best performers. The Texas Eagle went from 22.4% to 96.7%, and the California Zephyr, with an abysmal 5% on-time record in 2008, went up to 78.3%.[97] However, this improved performance also coincided with a general economic downturn, resulting in the lowest freight rail traffic volumes since at least 1988, meaning less freight traffic to impede passenger traffic.[98]

Another major reason for the slowness is that fast trains of the 1930s and 1940s were significantly set back by a 1951 Interstate Commerce Commission rule which required enhanced safety features for all trains traveling above a 79 mph limit.[21] Since the infrastructure required for cab signaling, automatic train stop and other enhancements was considered uneconomical in the sparsely populated American West at that time, this rule effectively killed further development of high speed rail outside of the Northeast, where the Pennsylvania Railroad and others had installed cab signaling beginning in the 1930s. No other English-speaking country adopted this rule, and while the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia all operate trains at 100 mph (160 km/h) or higher using conventional lineside signaling, few trains in the United States operate above 79 mph (127 km/h) outside of the Northeast Corridor. One notable exception is the Southwest Chief, which travels up to 90 miles per hour (140 km/h) along various stretches of its Chicago–Los Angeles route. However, positive train control (PTC) signaling is required to be implemented by 2015 under the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008, and it is sufficient to remove the 79 mph limit.[99] The Wolverine has already had some PTC signaling and other upgrades put in place to enable higher speeds, and PTC has proven to be a much less expensive method to provide enhanced signaling than earlier technologies used in the United States.

For the time being, slow speeds remain a major issue. In Britain, for example, the 393-mile journey from London to Edinburgh is completed in around four and a half hours (an average speed of around 87 miles per hour)[100]. In the USA, the 340-mile journey on the Cardinal from New York to Charlottesville takes some 7 hours,[101] an average of just under 49 miles per hour; other Amtrak trains are slower still. Even the flagship Acela service between New York and Boston only averages, in its three and a half hour journey, around 63 miles per hour[101], in large part due to the age of the trackage and catenary system, which has been undergoing renovation in stages since Acela's 2001 introduction. Also, some segments of track in the Northeast Corridor are too close together for the Acela carriages to safely tilt while maintaining FRA-mandated minimum space between trains on parallel tracks.

The comparison is even more stark when Amtrak trains' speeds are compared with the dedicated high-speed trains of China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and Spain. Frequency of trains even between major destinations in the USA (again outside the Northeast Corridor), compared with European standards, is extremely low – many long distance main lines in Europe operate to half-hourly frequencies throughout the day, whereas in the USA many major cities (such as Indianapolis and Dallas) have (at best) a daily intercity rail service.

For usage of Amtrak trains/routes: see List of Amtrak routes

The ridership for US intercity lines is again, compared with European/Japanese standards, remarkably low. The entire passenger count for a typical Amtrak intercity route would not match the passenger usage of a single modest station in Europe. For example, the route from Chicago to San Antonio (the Texas Eagle), taking in Fort Worth and other major cities and towns along its route, had a ridership in 2008 of just 251,518 passengers; while the relatively minor station of Lowestoft (population 55,000) in Suffolk, England had a patronage of over 410,000 for the same period. Some Amtrak routes (for example the "Heartland Flyer" with its ridership of only 80,892 per annum) have minuscule ridership compared with European standards. This discrepancy is due in large part to Amtrak's perceived (as mentioned above) lower federal funding priority compared to commercial aviation and the Interstate highway system, which in turn has traditionally resulted in far greater usage of the airlines and automobiles for the majority of intercity travel in the US. This perceived bias against Amtrak is an ongoing source of criticism and frustration for the strongest Amtrak supporters, who want Amtrak service, public/political favor and status to be closer to that of passenger rail service in other parts of the industrialized world.

Guest Rewards

Amtrak's loyalty program, Guest Rewards, is similar to the frequent-flyer programs of many airlines. Guest Rewards members accumulate points by riding Amtrak and through other activities, and can redeem these points for free or discounted Amtrak tickets and other rewards.

Freight

Amtrak Express provides small-package and less-than-truckload shipping among more than 100 cities. Amtrak Express also offers station-to-station shipment of human remains to many express cities. At smaller stations, funeral directors must load and unload the shipment onto and off the train. Amtrak hauled mail for the United States Postal Service and time-sensitive freight, but discontinued these services in October 2004 when the contract was lost. On most parts of the few lines that Amtrak owns, trackage-rights agreements allow freight railroads to use its trackage.

Commuter services

Through various commuter services, Amtrak serves an additional 61.1 million passengers per year in conjunction with state and regional authorities in California, Connecticut, Maryland, and Washington. Amtrak's Capitol Corridor, Pacific Surfliner (formerly San Diegan), and San Joaquin are funded mostly by a state transit authority, Caltrans, rather than the federal government.

Classes of service

Amtrak has a variety of cabins that suit a variety of needs. Classes are similar to those used by airlines.

First Class service is currently offered on the Acela Express only. Previously First Class was offered on the Northeast Direct (predecessor to the Northeast Regional) as well as the Metroliner up until that service's discontinuation in 2006. First Class passengers have access to Amtrak ClubAcela lounges in Washington D.C., Philadelphia, New York and Boston (lounges offer complementary drinks, personal ticketing service, lounge seating, conference areas, computer/internet access and televisions tuned to CNN). At the Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., ClubAcelas, passengers can board their train directly from the ClubAcela. In Philadelphia, passengers use an elevator while in Washington, passengers leave through a side door leading to the tracks. Seats are larger than those of Business Class and come in a variety of seating modes (single, single with table, double, double with table and wheelchair accessible). First Class is located in separate cars from the other classes. First Class includes complimentary meal and beverage service along with free newspapers and hot towel service. First Class seats are set in a 1x2 configuration. There are two attendants per car.

Sleeper Service rooms are considered First Class on long distance trains. Rooms are classified into roomettes, bedrooms, family bedrooms and accessible bedrooms. With the price of a room comes complimentary meals and attendant service. At night, rooms turn into sleeping areas with fold-down beds and fresh linens. Complimentary bottled water, newspapers and turn down service is included as well. Sleeper car passengers have access to the entire train. Sleeper passengers also have access to the Club Acela lounges in stations along the Northeast Corridor and access to the Metropolitan Lounges in Chicago, Miami, New Orleans, Portland (OR), and Minneapolis/Saint Paul.

Business Class is the minimum class of service on the Acela Express and is offered as an upgrade on Regional and other short to long distance trains. Business Class seats are larger than those in coach. Business Class passengers have easy access to the cafe car. They also receive complimentary non-alcoholic beverages and free newspapers. Business Class seats all have power outlets for electronics. Business Class seats are located in different areas depending on the train. On some trains, Business Class is located at the front of the Café Car. These seats are in a 1x2 style and feature leather upholstery, cup holders and leg rests. These seats also recline to a more "sofa recliner style." The other type of Business Class seat is located in an actual Business Class car. These seats are organized in a 2x2 style and feature more legroom than the coach seats in the other cars.

Reserved Coach is the standard class of service on most Amtrak trains (except Acela). Coach seats are set in a 2x2 configuration and are comparable to economy class seating on airlines (although usually with significantly more legroom). All ticketed passengers are guaranteed a seat, although unlike on Canada's Via Rail and some long distance train services in Europe, passengers are not assigned to a specific seat before boarding. If the train is not sold out, passengers are usually permitted to purchase tickets the day of departure, or in some cases on-board.

Unreserved Coach seating is offered on a first come, first served basis on some of Amtrak's shorter distance and commuter oriented routes. Until 2005 certain Northeast Regional trains were unreserved, running alongside standard reserved trips. The hourly Clocker trains that ran from New York to Philadelphia until late 2005 were also unreserved. Currently the Pacific Surfliner, the Capitol Corridor, the Hiawatha, and the Keystone Service between Harrisburg and Philadelphia are the only trains to offer unreserved coach seating. Unreserved coach is also used as a designator when Amtrak through-books an itinerary with a regional transit operator's commuter service (such as New Jersey Transit's Atlantic City Line)

Trains and tracks

Most tracks on which Amtrak operates are owned by freight railroads. Amtrak operates over all five Class I railroads in the United States, as well as several regional railroads and short lines, such as Pan Am Railways, the New England Central Railroad, and the Vermont Railway. Other sections are owned by terminal railroads jointly controlled by freight companies or by commuter rail agencies. The arrangement has two notable impacts on Amtrak operations. The host railroad is responsible for maintenance and occasionally Amtrak has suffered service disruptions from untimely track rehabilitation. When host railroads have simply refused to maintain their tracks to Amtrak's needs, Amtrak occasionally has been compelled to pay the host to maintain the tracks. Also, Amtrak enjoys priority over the host's freight traffic only for a specified window of time. When a passenger train misses that window, host railroads may (and frequently do) direct passenger trains to follow lumbering freight traffic, severely exacerbating even minor delays and exposing the host railroad to financial penalties by law.

Tracks owned by Amtrak

Along the Northeast Corridor and in several other areas, Amtrak owns 730 route-miles of track (1175 km), including 17 tunnels consisting of 29.7 miles (47.8 km) of track, and 1,186 bridges (including the famous Hell Gate Bridge) consisting of 42.5 miles (68.4 km) of track. Amtrak owns and operates the following lines:[102]

Northeast Corridor

The Northeast Corridor between Washington, D.C. and Boston via Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark, New York and Providence is largely owned by Amtrak, working cooperatively with several state and regional commuter agencies. Amtrak's portion was acquired in 1976 as a result of the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act.

- Boston to the Massachusetts/Rhode Island state line (operated and maintained by Amtrak but owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

- 118.3 miles (190.4 km), Massachusetts/Rhode Island state line to New Haven, Connecticut

- 240 miles (390 km), New Rochelle, New York to Washington, D.C.

The part of the line from New Haven to the New York/Connecticut border (Port Chester/Greenwich) is owned by the state of Connecticut, while the portion from Port Chester to New Rochelle is owned by the state of New York. The Connecticut Department of Transportation and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority operate this line through Metro-North Railroad.

Philadelphia to Harrisburg Main Line

This line runs from Philadelphia to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. As a result of an investment partnership with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, signal and track improvements were completed in October 2006, and now allow all-electric service with a top speed of 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) to run along the corridor.

- 104 miles (167 km), Philadelphia to Harrisburg (Pennsylvanian and Keystone Service)

Empire Corridor

- 11 miles (18 km), New York Penn Station to Spuyten Duyvil, New York

- 35.9 miles (57.8 km), Stuyvesant to Schenectady, New York (operated and maintained by Amtrak, but owned by CSX)

- 8.5 miles (14 km), Schenectady to Hoffmans, New York

New Haven-Springfield Line

- 60.5 miles (97.4 km), New Haven to Springfield (Amtrak Northeast Regional and Amtrak Vermonter and especially the New Haven–Springfield Shuttle).

Other tracks

- Chicago–Detroit Line – 98 miles (160 km), Porter, Indiana to Kalamazoo, Michigan (Blue Water and Wolverine)

- Post Road Branch – 12.42 miles (19.99 km), Post Road Junction to Rensselaer, New York (Lake Shore Limited)

Amtrak also owns station and yard tracks in Chicago; Hialeah (near Miami, Florida, leased from the state of Florida); Los Angeles; New Orleans; New York City; Oakland (Kirkham Street Yard); Orlando; Portland, Oregon; Saint Paul, Minnesota; Seattle; and Washington, D.C.

Amtrak owns the Chicago Union Station Company (Chicago Union Station) and Penn Station Leasing (New York Penn Station). It has a 99.7% interest in the Washington Terminal Company[103] (tracks around Washington Union Station) and 99% of 30th Street Limited (Philadelphia 30th Street Station). Also owned by Amtrak is Passenger Railroad Insurance.[104]

Other infrastructure:

|

|

|

Amtrak Services (Quick Reference)

| Service | Route |

|---|---|

| Acela Express | Boston – D.C. |

| Adirondack | Montreal – New York City (via Albany) |

| Amtrak Cascades | Vancouver – Eugene, Oregon (via Portland, Oregon and Seattle, Washington) |

| Auto Train | Lorton (Washington, D.C. area)- Sanford (Orlando, Florida area) |

| Blue Water | Chicago – Port Huron |

| California Zephyr | Chicago – Emeryville (San Francisco) |

| Capitol Corridor | Auburn – Sacramento – San Jose (via Oakland) |

| Capitol Limited | Chicago – Washington, D.C. (via Cleveland, Ohio and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) |

| Cardinal | Chicago – New York (via Indianapolis/Cincinnati/D.C.) |

| Carl Sandburg | Chicago – Quincy |

| Carolinian | New York – Raleigh – Greensboro - Charlotte |

| City of New Orleans | Chicago – New Orleans |

| Coast Starlight | Seattle – Los Angeles (via Sacramento/Oakland) |

| Crescent | New York – New Orleans (via Atlanta) |

| Downeaster | Portland, Maine – Boston |

| Empire Builder | Chicago – Portland, Oregon/Seattle (via Spokane) |

| Empire Service | New York – Niagara Falls (via Albany) |

| Ethan Allen Express | New York – Rutland (via Albany) |

| Heartland Flyer | Oklahoma City – Fort Worth |

| Hiawatha | Chicago – Milwaukee |

| Hoosier State | Chicago – Indianapolis |

| Illini | Chicago – Carbondale |

| Illinois Zephyr | Chicago – Quincy |

| Keystone Service | New York – Harrisburg (via Philadelphia) |

| Lake Shore Limited | New York – Boston – Chicago (via Albany) |

| Lincoln Service | Chicago – St. Louis |

| Maple Leaf | New York – Toronto |

| Missouri River Runner | St. Louis – Kansas City |

| New Haven–Springfield Shuttle | New Haven – Springfield |

| Northeast Regional | Boston – New York – Washington – Newport News- Lynchburg, Virginia- Springfield |

| Pacific Surfliner | San Luis Obispo – Los Angeles – San Diego |

| Palmetto | New York – Savannah |

| Pennsylvanian | New York – Pittsburgh (via Newark, Philadelphia, Harrisburg and Altoona) |

| Pere Marquette | Grand Rapids – Chicago |

| Piedmont | Charlotte – Raleigh |

| Saluki | Chicago – Carbondale |

| San Joaquin | Bakersfield – Oakland / Sacramento |

| Silver Meteor | New York – Fayetteville – Miami |

| Silver Star | New York – Raleigh – Tampa – Miami |

| Southwest Chief | Chicago – Los Angeles |

| Sunset Limited | Los Angeles – New Orleans |

| Texas Eagle | Chicago – Los Angeles (through San Antonio and Dallas) |

| Vermonter | Washington – St. Albans |

| Wolverine | Chicago – Detroit – Pontiac |

Motive power and rolling stock

See also

- Amtrak paint schemes

- Amtrak Arrow Reservation System

- Amtrak Police

- Amtrak California, partnership with

- Caltrans

- Amtrak Cascades, partnership with

- Washington State DOT

- Oregon Department of Transportation

- List of Amtrak stations – alphabetical by city name

- List of Amtrak station codes – alphabetical by 3-letter ticketing code

- Positive train control

- Railway Museum of Greater Cincinnati

- Superliner (railcar)

- Thruway Motorcoach

- Via Rail

Rail Companies of Interest

- Amtrak Express Parcels (UK)

- Auto-Train Corporation — Pioneer of car-on-train service.

- Amtrak's Auto Train.

- Mid America Railcar Leasing

Rail Disasters

- 1995 Palo Verde, Arizona derailment

- 1999 Bourbonnais, Illinois train accident

- 1987 Maryland train collision

- 1993 Big Bayou Canot train wreck

References

Notes

- ↑ Amtrak (2000-07-06). "Amtrak Introduces Service Guarantee and New Corporate Brand Identity At Event At Los Angeles Union Station". Press release. http://www.trainweb.com/news/2000g06a.html. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Amtrak National Facts". Amtrak. http://web.archive.org/web/20080120101132/http://www.amtrak.com/servlet/ContentServer?pagename=Amtrak/am2Copy/Title_Image_Copy_Page&c=am2Copy&cid=1081442674300&ssid=542. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ↑ "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2008 District of Columbia." Amtrak. Retrieved on September 16, 2009.

- ↑ The Past and Future of U.S. Passenger Rail Service, sec. 4 n.21 (September 2003).

- ↑ "Web archive of U.S. House of Representatives report". http://web.archive.org/web/20061110231722/http://www.house.gov/transportation/rail/04-30-03/04-30-03memo.html.

- ↑ Frank N. Wilner, United Transportation Union newsletter.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Amtrak Fact Sheet

- ↑ "Inside Amtrak - News & Media - News Releases - Latest News Releases". Amtrak. http://www.amtrak.com/servlet/ContentServer?pagename=Amtrak/am2Copy/News_Release_Popup&c=am2Copy&cid=1178294234716. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ↑ Trains magazine, March 2009, Trains' formula for fixing Amtrak, article by Rush Loving, Jr.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Schafer, Mike. (2001). The American Passenger Train. Saint Paul, Minnesota: MBI. pp. 20, 97, 99–102, 104, 106, 112, 119. ISBN 0760308969.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Carper, Robert S. (1968). American Railroads in Transition; The Passing of the Steam Locomotives. New York, New York: A. S. Barnes. pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel H. (2008). "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to Present". MeasuringWorth. http://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/compare/. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ Hosmer, Howard; et al. (1958) Railroad Passenger Train Deficit. Interstate Commerce Commission. Docket 31954. (Report).

- ↑ Daughen, Joseph R.; Binzen, Peter (1971). The Wreck of the Penn Central. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 213–214, 255, 310–311.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Morgan, David P. Who Shot the Passenger Train? Trains, p.14–15, 20–21 (April, 1959)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Slason Thompson, A Short History of American Railways, Books for Libraries Press: Freeport, NY (1925, reprinted 1971), p. 324–391, 405.

- ↑ "Railroads". Funk & Wagnall's New Encyclopedia. History.com. 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20080423135710/http://www.history.com/encyclopedia.do?articleId=220263. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ↑ "United States". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. February 1, 2010. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ↑ William Wendt (July 30, 2007). "Hiawatha dieselization". Yahoo Groups. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/steam_tech/message/54227. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ John Gruber and Brian Solomon (2006). The Milwaukee Road's Hiawathas. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0760323953.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Ask Trains from November 2008". Trains Magazine. December 23, 2008. http://www.trains.com/trn/default.aspx?c=a&id=4424. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ↑ Shafer, Mike, supra at 125. Previously, individual states made those judgments, and the reform that came about with the Transportation Act of 1958 was intended to streamline the process.

- ↑ "Brief History of the U.S. Passenger Rail Industry". http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/adaccess/rails-history.html.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Myths of Amtrak by the NARP, point 4, "4. Myth: Private Freight Railroad companies subsidize Amtrak."". http://www.narprail.org/cms/index.php/resources/more/myths/.

- ↑ Wikipedia article on History of Interstate Highways

- ↑ Luberoff, David. Amtrak and the States. Governing Magazine. p.85 (November 1996).

- ↑ Sagert, Kelly Boyer. 2007. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 218. http://books.google.com/books?id=9feBCLNhcFQC&pg=PA218&lpg=PA218&dq=%22georgia+railroad%22+join+amtrak&source=web&ots=2DDMbkagKO&sig=9gPH_kdoFGGNOAvBbvd95xF2l-c&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA218,M1.